The longing for leisure

According to Aristotle, the highest purpose of civilization was to create meaningful forms of leisure for its citizens — and for the individual the ideal to be sought was leisure as an exploration of the good life. Leisure as it was first defined during that Golden Age was the ultimate destination and a necessity for the development and renewal of a democratic society.

Despite 20 centuries of astonishing technological development, western civilization has lost much of the insight and ideals of the ancient Greeks. Today most of our leisure time is given over to amusements, to a hiatus from the work-a-day world. Yet the longing for the good life, for personal renewal, for enrichment and discovery, has never been greater. In an age in which every place is electronically accessible but remote from our touch, we seek remote places which offer access to new perspectives, discoveries, and encounters.

The creation of a destination

A destination is first and foremost an imagined place, an ideal experience we hope for in the future and cherish from the past. As an ideal place, the destination cannot simply be appreciated passively but requires participation in an experience which is, by definition, transitory. Physically and psychologically the guest must leave a familiar world of routines to enter a novel realm of discovery and renewal. It is inevitable that the guest will eventually return to that _world, but with the possibility that the place visited will provide a transformative experience. More often than not, it is the promise of renewal that summons a return to a special place, remembered during the height of occupational activity as the beginning of a preferred destiny.

Creating a destination, a setting for leisure and renewal, is therefore a special kind of place making. The destination as derived from its Latin root destinare represents both a journey and a promise, the belief that there is both a rhyme (poetic) and reason (noetic) to one’s life. The destination is at once the portal, way station, and terminus of a hopeful journey toward renewal, re-creation, and transformation.

Destination architecture combines the architectonics of a place, a journey, and a dream. To reveal this hidden structure requires a framework for understanding the visitor’s experience, beginning with the contemplation of a visit, followed by the experience itself, and concluding with the recollection of the treasured place.

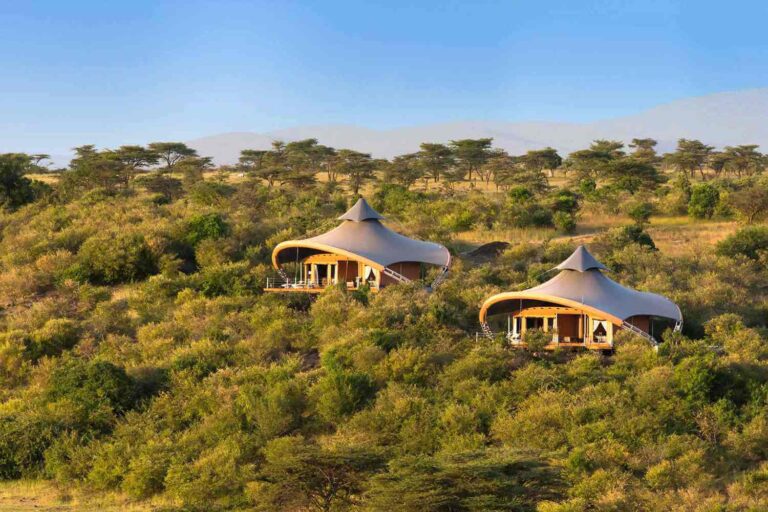

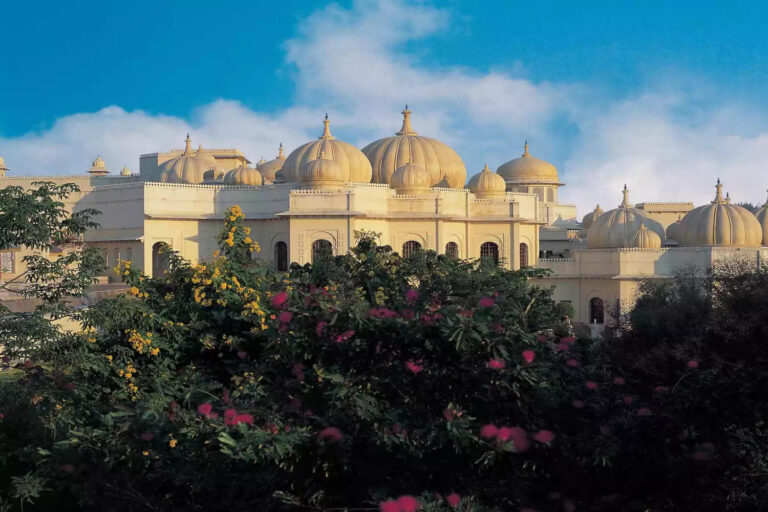

The imagery of a distant place

Any journey begins with the hope for fulfilment that might be provided by a special place, distinct and distant from the familiar surroundings of the everyday world. These places are not necessarily far away geographically, but must provide the imagery of a distant place. Long before the arrival experience, the expectant visitor pores over travel books, maps, and brochures. The implicit search is for an image that connotes what one believes can be found in this distant place — through its culture, nature, or history.

The experience of a transitory place

Neither the dream of a far-off place nor the journey to the destination ends with the Travellers’ long awaited arrival, for what is most unique about the destination place is its transitory nature. It is within this context that the destination is transformed from an image into a place. Remarkably, it is the transitory nature of the visit that provides the structure for place making. The architectonics of the destination involves an orchestrated sequence of transitional settings that provide a framework in which the visitor is offered the opportunity to enter a realm removed from the temper of everyday life. Several elements serve to define this transitional structure.